Wine is not my work. It’s my life. – Simone Castelli

I visited Veneto just a little while ago. Fortunately, I was privileged to return to Italy a few weeks later. At the airport, a passport control agent commented, “You were here last month,” as if it was a bad thing. If you ask me, you can never get enough of Italy.

On this trip, I was invited to spend time in Soave and Colli Euganei, followed by a few days in Maremma, a small but breathtakingly beautiful region in southern Tuscany that is experiencing a renaissance.

Maremma is only a two-hour drive southwest of Florence. Once the land of outlaws, cowboys and sheep farmers, it is now a significant wine producing region. The area has close to four thousand acres of vineyards in production. It’s three hundred wineries produce roughly one hundred and forty thousand cases annually.

The region is impossibly picturesque. Puffy clouds are seemingly painted on the azure sky. The vineyards are sprinkled with neon-red poppies, dazzling wild flowers and bright yellow “ginestra” bushes. It looks like a postcard.

In the heart of the Maremma region are the villages of Magliano and Scansano. They are surrounded by idyllic rolling hills that are covered by olive groves, oak trees and lush vineyards. It quickly reminded me of California’s Central Coast.

As it turned out, I was right! It’s nicknamed “California of Italy.” Its Mediterranean climate features warm summer days and cool night breezes, moderated by Tyrrhenian Sea. Maremma is a grape grower’s paradise. The nearby sea creates a diurnal temperature shift. These textbook conditions allow for perfect physiological ripening of grapes, resulting in wines with fragrant fruit flavors. Maremma’s long autumns, mild winters and wet springs complete the picture-perfect conditions.

The soil types vary; loam, clay and sand, with plenty of limestone, and rock, that give the area’s wines delicate, perfumed characteristics and medium body structure.

The man often credited with discovering the region’s potential is Marchese Mario Incisa della Rocchetta, the founder of Sassicaia. His vision centered around wines made with classic Bordeaux varieties, blended with Tuscany’s signature Sangiovese.

In the last decade, the region’s wines have become a hip alternative to Chianti and the Sangiovese-based blends of Tuscany. Today, the terroir and coastal climate are attracting well-known winemakers from Tuscany, as well as acclaimed international vintners.

Maremma used to be an exceptionally boggy area, a motionless marshland. Its name derives from the Spanish word, Marisma, meaning “marsh.” In the past, this perilous land, besieged by bandits and disease-infested mosquitoes was an anathema. Poet Dante Alighieri’s once said that even the roughest creatures would find Maremma unfriendly.

The marsh was partially drained by the Etruscans, followed by the Romans. Finally, a millennium later, the reclamation of the land was completed during Benito Mussolini’s rule. His government’s policy of draining various unusable areas of Italy for agricultural and recreational use (Tuscany was a favorite vacation spot), served Maremma well. The area has come a long way from Dante’s unflattering portrayal.

Now, lavish seaside vineyards cover the landscape. Famous wine producers, restaurateurs and hoteliers have replaced the outlaws. Extravagant hotels and rustic “agriturismo” (renovated farmhouses) accommodations have sprung up among the vines. Producers from all over the world have taken note of the grape-friendly coastal climate and low-cost land. New York-based culinary giants, Joe Bastianich and Mario Batali, have purchased vineyards here, joining local producers such as the Antinori, Biondi-Santi, Bolla, Cinelli, Frescobaldi, Mazzei and Moretti families, amongst others.

Southern Tuscany is strikingly different from the north. While its neighboring region boasts such popular destinations as Florence and Siena, Maremma is far more insulated and private. Far fewer wineries are open to the public. The region’s feel is more open and spacious than the more densely populated north. The coastal area is vast and largely undeveloped. It stands in stark contrast to the condensed, manicured Northern provinces.

Maremma was upgraded to a DOCG status in 2011. The blends are required to be comprised of at least 85% Sangiovese. The remaining 15% is typically supplemented by local varieties such as Aleatico, Alicante, Canaiolo Nero, Ciliegiolo, Malvasia, Nera Mammolo, or Nero Francese. Occasionally, Cabernet Franc, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot or Syrah are used for blending. Only a handful of vintners craft 100% Sangiovese wines.

Sangiovese is the grape that is the basis for many of Tuscany’s makes many world-class wines. Perhaps best known are Super-Tuscans, Chianti, Vino Nobile di Montepulciano, Brunello di Montalcino and Vin Santo.

Principal white varieties include Ansonica, Chardonnay, Malvasia, Sauvignon Blanc, Trebbiano, Vermentino and Viognier.

I visited a number of interesting vineyards and wineries. Two made particularly strong impressions. They represent distinct and contrasting examples of what Maremma offers.

A noteworthy winery was Val Delle Rose. Originally established in 1883, it was purchased by the Cecchi family in 1996. Located in a small village of Poggio la Mozza, it only had 60 acres under vine. Armed with soil studies, Cecchies knew it was a terroir treasure. They eventually quadrupled the vineyards.

As a I strolled through Val Delle Rose’s meticulously manicured grounds, I wondered if I had stepped into Silicon Valley. This was no rural winery that time forgot. Armed to the hilt with state-of-the-art technology, the gravity flow facility looked like something one would find in the middle of Napa. Nothing is left a chance in the vineyard or the cellar. Use of the latest technological equipment allow for maximum quality control. It is the largest Scansano-area winery.

They make five wines:

- Aurelio – in its first vintage, this Merlot blend is an homage to a namesake scenic road gracing the coastline of Tuscany. This medium-bodied wine is rich and concentrated. Its spicy, savory flavors are expertly framed by rich, dark chocolate. The tannins are soft and supple, and the finish, lengthy.

- Coevo – without a doubt, the wine of the trip. Meaning “contemporary” Coevo underscores the notion of modern winemaking along with timeless quality. It is a fusion of grapes from Maremma and Cecchi’s Chianti property. Expressive nose of dry herbs, flowers and pomegranate. Hints of cocoa powder are followed by dark fruit. It shows off conspicuous, yet cohesive tannins along with vanilla infused, well-integrated wood. The finish is marvelously long and satisfying.

- Litorale – the best Vermentino blend that I have tasted during this trip. Rounded by Sauvignon Blanc, this heady, floral and citrus-driven wine has just enough salinity and minerality to balance out a fragrant bouquet. The winemaker achieved a minor miracle for a wine that is produced in a hot region – good acidity. This is solid proof that, with the right viticulture and technology, one can produce great white wines in the southern regions.

- Morellino di Scansano – not your father’s Morellino, it’s sleek, modern and beguiling. Earthy notes are supplemented by bright red fruit reminiscent of the cherries that grow in the area. Juicy and sexy, it’s a wine that vividly expresses the varietal.

- Poggio al Leone – is aged for a minimum of one year, and arguably, is a great candidate for the cellar. Cheerful red, energetic, perfumed, solidly structured and well-endowed, it embraces Sangiovese in all its glory.

Valle Del Rose’s viticulturalist spoke extensively of the importance of working the land to make better Sangiovese. His work is a validation of the concept that “wine is grown in the vineyard.”

The winery’s hospitality was above and beyond the usual. Upon arrival, we were treated to an insanely delicious blackberry pie and espresso. They offer several consumer tasting experiences, ranging from just wine, to charcuterie, or handmade pasta pairings; all prepared by their chef.

The wines are fantastic—elegant, expertly crafted and available in the U.S.

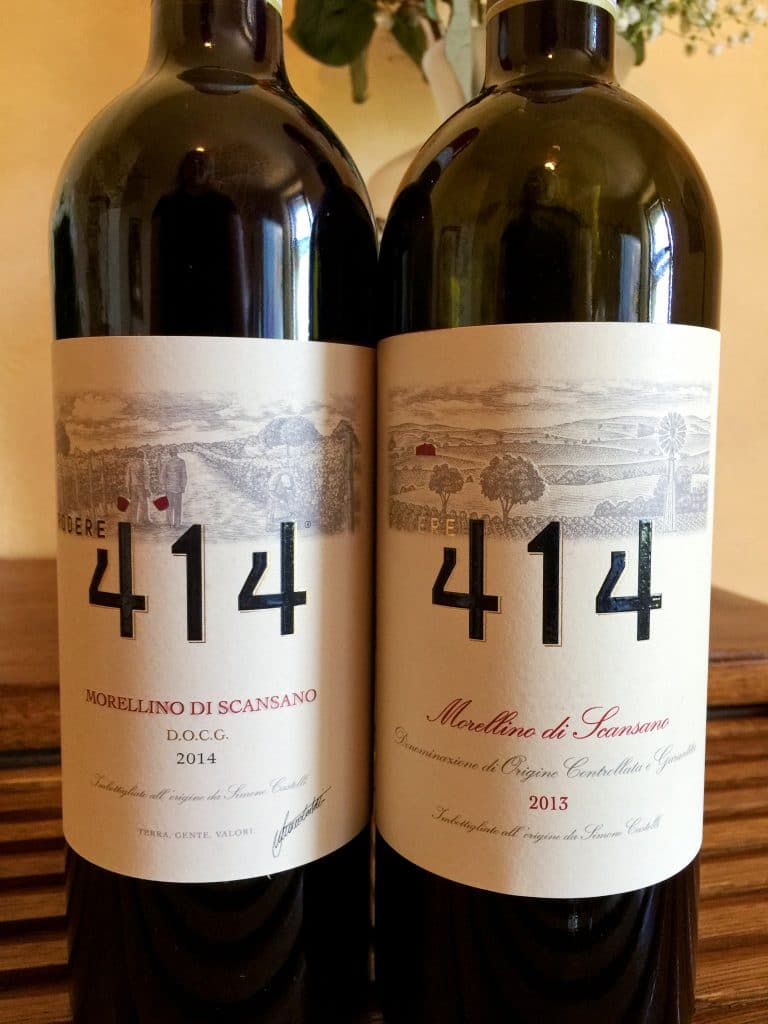

One other visit made an indelible impression—Podere 414. The winery is named after the number given to the farm during a 60’s era land reform project that resulted in land distribution to local families. The farmland consisted of rough, challenging terrain that was consider only suitable for subsistence farming. It was that piece of land that Simone Castelli, an oenology graduate, along with his father Maurizio, and grandfather Giuseppe, fell in love with. After a long search, the trio stumbled onto this unlikely spot. In 1998, Podere 414 was born.

The 120-acre property with has 50 acres under vine. Its hills overlook Montiano village. It is planted to predominantly Morellino along with a smattering of Colorino and Ciliegiolo. Simone makes roughly 4,000 cases of wine from his organically farmed property. His father, a renown Tuscan enologist, with projects in Friuli, Chile, New Zealand and California, oversees the viticulture.

Simone, crafts a Rosato, a Morellino and lovely Passito which is made in the Solera method.

Rosato—“Flower Power” is a tribute to poet, Allen Ginsberg, who coined the during the wild and crazy sixties. It’s lighthearted and playful, a perfect aperitif.

- Morellino – a blend of 85% of Sangiovese, rounded by Ciliegiolo, and for freshness, Alicante and Colorino. Bright and aromatic, its expressive and delicious.

- Passito – only a tiny amount of this wine is produced. It is made with indigenous Aleatico grapes. Aleatico wines are made using dry fruit resulting in a wine with higher alcohol that doesn’t require fortification.

It’s clear that Simone is a free thinker, a rebel with a cause who refuses to follow trends. Sangiovese, like fashionable Pinot Noir in the US, is the grape du jour. Castelli is none too pleased with this trend. He is all about authenticity, not auspiciousness. He works himself to the bone and never stops asking questions, experimenting and growing as a vintner. Despite the harsh economic realities of the Italian wine industry, he refuses the cynical option to make average, quaffable wines. “Winemaking isn’t my job, it’s my life”—he states with a solemn look.

The 2014 vintage in Italy was rough. Even seasoned winemakers were ready to slash their wrists. Nothing went right the vintage. Bacchus let the vintners feel every painful minute during this miserable season. It was a vintage that separated men from boys, and tested every winemaker’s skills and patience. To add insult to injury, Simone’s oenologist quit in the middle of what was already an unmitigated disaster. Castelli worked 18-hour days, making multiple passes through vineyards. He discarded under-ripe grapes by hand, praying that he has enough to survive. One morning he woke up covered in hives, from sheer unrelenting stress. He learned a lot about himself and his vineyard that year.

In the end, he succeeded. I tasted his 2014 before I learned the story of his valor. It was a wonderful effort, earnest, delineated, restrained and flawlessly executed. I would have never known what that bottle represented; of the blood, sweat and tears that went into its production. It tasted like a great intellectual exercise in varietal prowess, with a generous dollop of great red and black fruit for a measure of fun.

I treasured my time with Simone. I valued his intensity and self-honesty. It was refreshing to see an abundant talent so focused on doing the right thing.

By now you are probably asking yourself—why is there a word dilemma in the title of the article?

The entire time that I was there, the single theme kept coming up—how do lesser known areas distinguish themselves?

Maremma, as many smaller wine regions, has a marketing problem. Most wine professionals, let alone average consumers, have little knowledge of these vintners. Think of it as Edna Valley of California, a region produces striking chardonnays that no one knows about. The parallels of many lesser known wine regions are staggering. Often, they make unique, (mostly) good-quality, extremely inexpensive wines that are entirely unknown beyond their regional borders.

It is a dilemma of enormous magnitude and consequences. These regions desperately need exposure to greater markets in order to generate the resources that would facilitate the overall health, growth and longevity of their brands.

I thought I would ask you, the reader, to participate in solving this conundrum, to do your part. Have you ever heard of Maremma before? If not, now you have.

Be proactive with your wine shops, restaurants and wine publications. Ask for wines that are esoteric, off the-beaten-path, different altogether.

Forgo the safety of your well-worn Chardonnay or Shiraz, step out of your comfort zone and reach out for wines that you never knew existed. Who knows, you may just enjoy the heck out of them. Put a smile on a face of a producer from a distant land. Know that you have made a difference.

You must be logged in to post a comment.